Open House for Butterflies is a book for children and the people who love them; it was written by Ruth Krauss, with illustrations by Maurice Sendak, and first published in 1960. Open House for Butterflies has been reprinted again and again, and I keep a copy near my desk, for smiles. The little book is full of words of wisdom, the kind that blossom and flourish in places where young children share their observations of the world. Several times over these past weeks and months I turned to the opening page, with plenty of white space framing a little drawing and a single line of text: A screaming song is good to know in case you need to scream.[1]

Nobody expected this presidential campaign to be a pleasant experience, but who would have thought that so much of our public discourse would be so utterly indistinguishable from the worst of so-called reality tv? A screaming song is good to know in case you need to scream. I don’t know any screaming songs, do you? I’ve screamed Rocky Top at Neyland Stadium as though my blood ran orange, but that’s not a screaming song. And I don’t think there is one in the hymnal, do you? I imagine a screaming song would be a fine opportunity to cuss like a sailor without the bad language; people could shout the song together and yell out all the rage, the wrath, the anger, the pain, the fear and frustration, and it would clear the atmosphere like thunder and lightning at the end of a day of thick heat. And then we would sit there with our soar throats, exhausted, and perhaps we would begin to find the words the other could hear, and perhaps we would begin to listen.

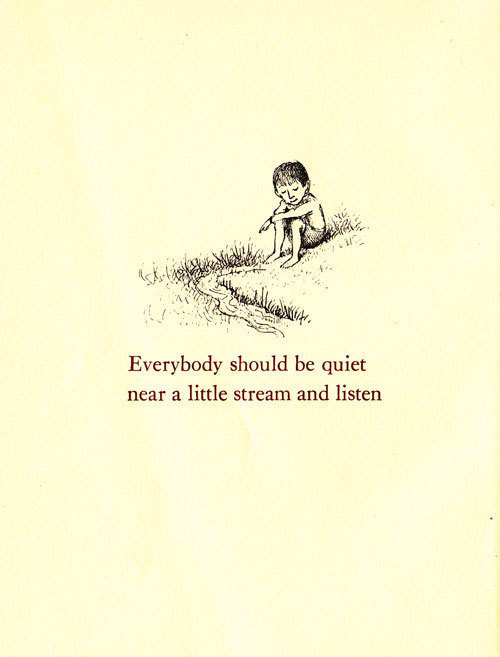

A few pages into Open House for Butterflies is one of my favorite morsels of wisdom. There’s a drawing of a little boy, sitting on a hill, with his eyes closed, next to a little stream. And again, just one line of text: Everybody should be quiet near a little stream and listen.[2] I imagine the boy is listening to the water running over the rocks, the insects rustling in the grass, the wind playing with the leaves in the trees, and the faint sound the air makes when it becomes breath in his nostrils. He’s listening to all there is in this particular moment. I love this little scene, the words and the drawing, because I love being quiet near water – near a little stream or on the lake or on the beach when the waves roll in – and I believe everybody should be there and listen, and not just once a year.

I also love this little scene because when I turn it, it reminds me that you and I and everybody else are all little streams in the mighty river of life, and how very good it is when every now and then somebody is quiet near us and listens. And when I turn the image one more time, it brings to mind how the Bible is like a stream, a mighty stream – deep and wide and full of wonders; ancient and yet new and different every time we listen. “Continue in what you have learned,” we heard in today’s reading from 2 Timothy, “knowing from whom you learned it, and how from childhood you have known the sacred writings that are able to make you wise for salvation through faith in Christ Jesus.”[3] This knowledge begins with our relationships with those who have been quiet by that mighty stream and listened and told us what they heard; this knowledge evolves into our own familiarity with those sacred writings, a familiarity not just with words, but with voices; with centuries upon centuries of struggle for understanding and discernment; a familiarity with this vast river of wonderings and insights regarding God’s presence and work in the world. We hear stories and philosophical musings, prayers and love poetry, proverbs and moral teachings, long lists of names, building instructions, prophetic indictments, riddles and parables. And for generations, people have turned to those sacred writings for all kinds of reasons: to find answers to pressing questions, prove a point, or win an argument, to formulate dogma or reconstruct ancient history, to get rich, to induce shame, to justify oppression and promote violence. But still, Paul of 2 Timothy gently insists, these writings, despite their questionable uses and outright abuses, are able to make us wise for salvation through faith in Christ Jesus. They can make us wise by cultivating in us a sense of wonder about God, the world, others, and ourselves.[4]

Fred Craddock once told a congregation,

I read something recently—I knew this, but I had forgotten about it—that years ago our ancestors used to go out walking, usually on a Sunday afternoon—sometimes alone, sometimes couples, sometimes the whole family—and they called it “going marveling.” Marveling. They would look for unusual rocks, unusual wild flowers, shells, four-leafed clovers, marvelous things. They would collect them, bring them back to the house, and show off the marvelous things they had found. Isn’t that a delightful thing, to go marveling?[5]

Craddock told them that when he read that and was reminded of that, he went marveling himself. I’ll tell you later what he found. I want us to stay a little longer with that lovely phrase, going marveling. It reminds me very much of the little boy, sitting quietly by the little stream, listening, hearing things he hadn’t noticed before, marvelous things he’d take back to the house and share. When we listen to the Scriptures in wonder, says William Brown, “not only does the text fall open to the reader, the reader falls open to the text.” There is a solitude at the heart of that encounter between Scripture and listener, but it doesn’t happen in isolation. It takes place in communion with others, in which fresh insights are shared and new relationships are formed. Reading with wonder, listening with wonder broadens and deepens the community of listeners and readers.[6]

In the passage from 2 Timothy we heard this morning there is a word that is incredibly rare; it’s used only once in the entire Bible. It’s a little word that has had to carry a lot of weight in debates about the Scriptures and how they are the Word of God. In the translation we heard, v. 16 says, “All scripture is inspired by God and is useful for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness.” The reference is to the Jewish sacred writings that were considered authoritative at the time, long before the apostolic writings were collected and became what we know as the New Testament. 2 Timothy was part of a push against tendencies among some Christian teachers to dismiss the books of Moses, the prophets, and other sacred texts as inferior or outdated. These writings, the apostle insists, are able to make you wise for salvation through faith in Christ Jesus, they are useful for teaching and all manner of other things, and they are inspired by God. Some hear inspired and think of heavenly dictation, others think of writers using their own words to communicate what they heard God say, and again others think of some moment akin to being kissed by a muse that gives a writer something to write about. The NIV translates more literally and less traditionally, “all Scripture is God-breathed.” It’s a fine translation that frees us to listen again in wonder and to go marveling. All Scripture is God-breathed… When you sit with this image of God breathing, what comes to mind?

I think of the moment, you can read about it in Genesis 2, when the Lord God formed the human from the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and the human became a living being. I wonder if the apostle is saying the sacred writings are alive with the breath of God just as humans are—and wouldn’t that mean that we have to let them breathe? We sit quietly by the wide stream of Scripture, listening, waiting expectantly as the Spirit of God moves among us, marveling at the new connections we discover in the sacred writings and among us, connections that reflect a wisdom beyond flat information, and more than wisdom, our salvation in Christ. And wouldn’t you agree that we need new connections alive with the breath of God more than anything in our time?

Yes, a screaming song is good to know in case you need to scream. But better yet to find a place beside the stream and listen.

So Fred Craddock told the congregation how he went marveling himself. “You know I live about a mile from here,” he told them.

If you walk down the railroad, it’s about a mile. So I left the house and went marveling. About a mile away I came upon a pavilion, and inside I saw a lot of people singing, praying, and reading scripture, and sharing their love for each other. They were vowing that they would—they promised to each other, and they promised to God—make every effort, God help them, to reproduce the life of Jesus in this place. And I marveled, how I marveled. And I said to myself, Look what I have found, right here, in this little building.[7]

For us, all the words of Scripture point ultimately to Jesus, the eternal Word of God, perfectly embodied in human life. So let us live to let his life be ours.