A woman took a walk in the fields, along the edge of the woods. It was a glorious spring-day, and the air was filled with the songs of more birds than I could name – warblers, wrens, and chickadees, robins, finches, and sparrows. It was a celebration of life unlike anything you could even begin to imagine in the cold, rainy days of November, but the woman didn’t notice; she was a botanist.

I smiled when I heard this on the radio, and I could see her walking along the edge of the woods, her eyes on the ground, fully absorbed in noticing and naming unique and spectacular little green things most of us would call weeds, or maybe wildflowers on a good day.

Attention is a strange and wonderful thing. The things I do attend to can so completely absorb my senses that I forget about time and everything else. And the things I don’t attend to in a sense don’t exist, at least not for me. We say we “pay attention,” suggesting that, when we are attentive, we are spending limited currency that should be wisely invested. We select a portion of all that’s there, and this thin slice of life becomes part of our reality, and the rest is consigned to the blurry margins and the shadows of oblivion.

Attention’s selective nature enables us to comprehend what would otherwise be chaos. We live in daily noise, some more so than others; we move through jungles of thoughts and ideas; we are drenched in feelings, constantly exposed to images; and attention allows us to protect our minds from overload and make our world from all that is happening.

About five years ago, the Washington Post published a great article. It was about a man playing the violine outside the Metro.

A youngish white man in jeans, a long-sleeved T-shirt and a Washington Nationals baseball cap. From a small case, he removed a violin. Placing the open case at his feet, he threw in a few dollars and pocket change as seed money, swiveled it to face pedestrian traffic, and began to play.

It was just before 8am on Friday, January 12, the middle of the morning rush hour. In the next 43 minutes, this violinist performed six classical pieces, and more than 1000 people passed by. No one knew it, but the fiddler standing against a bare wall outside the Metro in an indoor arcade was Joshua Bell, one of the finest classical musicians in the world, playing some of the greatest music ever written on one of the most valuable violins ever made.

His performance was arranged by The Washington Post as an experiment in context, perception and priorities – as well as an unblinking assessment of public taste: In a banal setting at an inconvenient time, would great art have the power to disrupt the ordinary, hurried routines of passersby?

The musician played masterpieces that have endured for centuries on their brilliance alone, including Bach’s Chaconne for solo violine, soaring music befitting the grandeur of cathedrals and concert halls.

The acoustics in the arcade proved surprisingly kind. The stone, tile, and glass somehow caught the sound and bounced it back round and resonant. The violin is an instrument that is said to be much like the human voice, and in this musician’s masterly hands, it sobbed and laughed and sang – ecstatic, sorrowful, importuning, adoring, flirtatious, castigating, playful, romancing, merry, triumphal, sumptuous.

The writer apparently was paying attention, but what about the commuters?

In the three-quarters of an hour that Joshua Bell played, seven people stopped what they were doing to hang around and take in the performance, at least for a minute. Twenty-seven gave money, most of them on the run – for a total of $32 and change. That leaves the 1,070 people who hurried by, oblivious, many only three feet away, few even turning to look. Now, if a great musician plays great music but no one hears, is it still great and beautiful art or is it just more noise on a busy Friday morning?

Bell said, “At a music hall, I’ll get upset if someone coughs or if someone’s cellphone goes off. But here, my expectations quickly diminished. I started to appreciate any acknowledgment, even a slight glance up. I was oddly grateful when someone threw in a dollar instead of change.” This is from a man whose talents can command $1,000 a minute.

Before he began, Bell hadn’t known what to expect, and he was nervous. “It wasn’t exactly stage fright, but there were butterflies; I was stressing a little (…) When you play for ticket-holders, you are already validated. I have no sense that I need to be accepted. I’m already accepted. Here, there was this thought: What if they don’t like me? What if they resent my presence ...” [1]

It’s not that they didn’t like him, they simply didn’t hear him. For the vast majority of commuters that Friday morning Joshua Bell’s music was only part of the background while their minds were focussed on getting their kids to school before work or how to impress their boss with a presentation later in the day.

American Philosopher William James wrote in 1890, “Everyone knows what attention is. It is the taking possession of the mind, in clear and vivid form, of one out of what seem several simultaneously possible objects or trains of thought. Focalisation, concentration of consciousness are of its essence. It implies a withdrawal from some things in order to deal effectively with others.”[2]

Attention allows me to focus on some things and filter out others; it distills the vastness of all that is into my world – and that means I must make choices. And making choices requires effort. And sometimes – too often, I’m afraid – I just take the lazy way out and drift along, and I squander precious currency on whatever happens to capture my awareness. Some of us like to blame technology for our diffused, fragmented state of mind, it’s the internet, it’s the cell phones, it’s texting and social media, but our seductive machines are not at fault. They each come with a power button.

Attention implies a withdrawal from some things in order to deal effectively with others. Thus the question is solely what it is we want to deal with, and that defines how often, how long, and how far we withdraw from other things.

I am talking about attention this morning because I believe it is at the heart of the question you asked me to address.

When we look back in history, we can see that dictators like Hitler were bad and we wonder why Christians didn’t stand up sooner to save the people. What about nowadays? When do we know to act, what to do? Where is our collective power?

When I first saw this question, my eyes skipped several words and jumped to “Hitler,” and I felt the pain and guilt and shame connected to that cursed name. I thought about the terror of those years, the unimaginable murder of Jews on an industrial scale, the war mongering, and how it all began in the hearts of human beings and with thoughts and words.

When we look back we can see… but the question that has haunted me since I started asking questions about my family, my people, my culture, my church, the question that I can’t answer is, why didn’t more people see when they didn’t have to look back? What was it they were paying attention to when they weren’t paying attention to the persecution of their neighbors? What were they paying attention to earlier when they weren’t paying attention to the transformation of public discourse into hate speech?

When we look back we can see… but the question that has haunted me since I started asking questions about my family, my people, my culture, my church, the question that I can’t answer is, why didn’t more people see when they didn’t have to look back? What was it they were paying attention to when they weren’t paying attention to the persecution of their neighbors? What were they paying attention to earlier when they weren’t paying attention to the transformation of public discourse into hate speech?

A pastor in Silesia, one of the many who had swallowed the junk food of so-called race theory and of Arian superiority, of German Christians and of “the Jewish question,” this pastor, this shepherd of his people, stood in the pulpit one Sunday morning and told the members of the congregation who didn’t qualify as Arian under the race laws, he told them to get up and get out – three times he told them, and we wonder why they didn’t all stand up and leave, we wonder why they didn’t all stand up and walk out together and leave him alone in his house of lies.

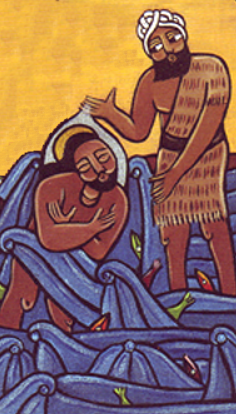

Then there was movement at the front of the sanctuary. There was a cross above the communion table, front and center, and the crucified Jesus came down from it and walked out, saying, “Truly I tell you, just as you did not do it to one of the least of these, you did not do it to me.”

What about nowadays? When do we know to act, what to do? I don’t know, what are you paying attention to?

Jesus points to the marginalized, the poor, and the suffering ones and says, “Can you see me now?”

Ezekiel, after lamenting the fall of the holy city, utters his severe indictment against the political class,

“Woe, you shepherds of Israel who have been feeding yourselves! Should not shepherds feed the sheep? You eat the fat, you clothe yourselves with the wool, you slaughter the fatlings; but you do not feed the sheep. You have not strengthened the weak, you have not healed the sick, you have not bound up the injured, you have not brought back the strayed, you have not sought the lost, but with force and harshness you have ruled them. So they were scattered, because there was no shepherd; and scattered, they became food for all the wild animals.”[3]

In a tradition of obligation that begins at Sinai, God’s covenant people are meant to be a community that is preoccupied with the well-being of the neighbor, and a community that is prepared to exercise public power for the sake of the neighbor, particularly the vulnerable neighbor in the person of the widow, the orphan, and the immigrant. Ezekiel insists that power cannot be sustained or give prosperity or security, unless it is administered with attention to the well-being of all who have little or no power. And Jesus asks, “Can you see me now?”

Everything depends on what we pay attention to. The real world in which God invites us to live is not the one made available by the rulers of this age, the masters of distraction, the peddlers of the simple answer, and the manipulators of our fears. The real world in which God invites us to live emerges when we let the good shepherd guide our attention, shape our imagination, and give us the courage to act.

[1] See the full article at http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/04/04/AR2007040401721.html

[2] William James, The Principles of Psychology, Chapter XI: Attention

[3] Ezekiel 34:2-5; the readings of the day were Ezekiel 34:11-16, 20-24 and Matthew 25:31-46

When we gather for worship, the sanctuary is filled with the sound of human voices - songs of praise, the spoken words of scripture and prayers, glorious anthems and "Little children, come unto me..."

When we gather for worship, the sanctuary is filled with the sound of human voices - songs of praise, the spoken words of scripture and prayers, glorious anthems and "Little children, come unto me..."