People were filled with expectation about John, questioning in their hearts whether he might be the Messiah. People were filled with expectation about Jesus, wondering whether he was the one or if they should wait for another. And people were filled with expectation about you when you were born, when you went to school, when you walked down the aisle in your long white dress, when you joined the church, when you started your new job. Expectations – they can lift you up and take you places you didn’t think were within your reach, and they can weigh you down and keep you from blossoming.

When little Billy was born, they proudly named him William Jefferson Cooper III, expecting without a question that he would follow in the footsteps of his father and grandfather by becoming an engineer, of course at Perdue, and taking over the family business. Imagine how much fun he had in his Senior year of highschool trying to convince his parents that he needed to go to Peabody because he wanted to be a teacher.

Expectations shape us in significant ways, whether they are our own or those of our parents and peers. They can give us wings or be the chains around our feet. Now perhaps you expect me to tell you which expectations are good or bad, or how to find the thin line that separates expecting too much from expecting too little and how to get it all just right. Well, I’m sorry to disappoint you.

What I do want to talk about is Jesus. It astounds me how he can step into this scene that is charged with messianic expectation and with visions of judgment and redemption, and he’s not being pulled this way or that way but follows his own path.

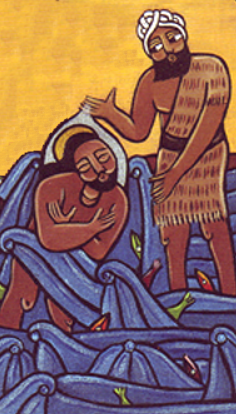

When he was about thirty years old, he came to the Jordan river, and he heard John the Baptist preaching repentance and forgiveness. When John warned the crowds of the wrath to come, Jesus was there and listened. When the crowds asked John, “What then should we do?” Jesus was there and took it all in. And when all the people were baptized, Jesus was washed in the river along with all of them, or perhaps I should say, along with all of us. The river of repentance is where we need to be, and Jesus gets in the water with us.

This is the Jordan, the river that Israel crossed after long years of wilderness wandering to enter the land of God’s promise. This river marks the border between what was and what shall be. Its waters wash away the dust, the dirt, the regrets and the shadow of all that we can’t undo. This is the river that prepares us to live as God’s people on God’s earth according to God’s will. And now Jesus gets in the water with us to make our lives his own, with all the distortions and the ugliness sin and lovelessness have caused, and to make his life ours. This moment in the river is the gospel in a nutshell: God bears all that breaks and destroys the fullness of life, and we are given a new beginning.

The curious thing about Luke’s account, though, is that he mentions Jesus’ baptism almost in passing.

Now when all the people were baptized, and when Jesus also had been baptized and was praying, the heaven was opened and the Holy Spirit descended upon him.

Luke makes sure we notice that Jesus is right there in the water with all the people, but the real news is the opening of heaven and the Spirit’s descent when Jesus was praying. Remember, this is a moment charged with messianic expectation, with proclamations of judgment in the air and visions of redemption – and Jesus prays. He stands amid the flurry of expectations of John and the crowd and, not to forget, his parents and siblings and friends, and he prays. Luke tells us, a voice came from heaven.

Now this is God speaking in the first person, which doesn’t happen very often in the scriptures, and if you think that it’s important to have all the words of Jesus printed in red, what color do you suggest for the voice from heaven? Gold letters? Or should our Bibles perhaps have a page break right after the comma so these precious words have a page of their own and our eyes don’t just keep reading as though getting to the end of the story were a matter of speed? An extra page might slow us down enough to notice that the voice from heaven doesn’t add to the already dense flurry of expectations with a solemn commission to Jesus to go and save the world. Instead we read this beautiful statement of love and delight, “You are my Son, the Beloved, with you I am well pleased.” And that’s it.

Perhaps we should insert another blank page at the end of this sentence to help us notice that this is all the voice from heaven says. No second sentence opening a whole new paragraph, “Now listen, Son, this is what I need you to do.” No parental reminder, “Now don’t you forget that, Son, or I won’t be pleased.” Only these words: You are my Son, the Beloved, with you I am well pleased.

Perhaps we should insert another blank page at the end of this sentence to help us notice that this is all the voice from heaven says. No second sentence opening a whole new paragraph, “Now listen, Son, this is what I need you to do.” No parental reminder, “Now don’t you forget that, Son, or I won’t be pleased.” Only these words: You are my Son, the Beloved, with you I am well pleased.

In Luke’s gospel, this scene by the river is followed by a long genealogy, name after name, generation after generation, layer upon layer of family history that define who Jesus is – except that Jesus’ true identity, his true name was spoken by the water by a voice from heaven.

There might be another reason, though, why Luke inserted this long genealogy right here, with names going back all the way to Adam: to help us recognize that Jesus is in the water with all the children of Adam and Eve. The river of repentance and forgiveness is where we need to be washed and refreshed, and he joins us so we each might know who and whose we are: God’s children, God’s loved ones, God’s delight.

This relationship defines us more profoundly than layers and layers of ancestry and history; and it does so because we’re not the ones who establish it. God’s love for us is the one relationship in life we can’t screw up. We can deny it, sure, we can ignore it, neglect it, forget it, and run away from it, but we cannot destroy it. Nothing we do or refuse to do will change who we are, God’s own and God’s beloved. Sometimes we forget. We forget because we’re busy. We forget because there are so many competing expectations from which we try to make a name for ourselves. We forget because life has convinced us that we are not worthy of love or too insignificant to even be noticed. We forget because pain and fear and shame bury our sense of self as God’s own and each other’s brothers and sisters.

What are we to do about that forgetfulness? Luke draws our attention to Jesus’ praying after he had been baptized. I don’t think he does this to suggest that heaven opened because Jesus prayed, but rather to remind us that the openness of heaven is a reality perceived with the openness of heart and mind that praying offers. He encourages us to pray in order to know in our bones and not forget that we are God’s own and each other’s brothers and sisters.

Martin Luther often struggled with a deep sense of unworthiness, and when he became discouraged and depressed he would say, “But I have been baptized.” The prayer of a desperate man hanging on to hope. He even wrote it on a slip of paper he pinned to the wall above his desk, “I have been baptized.” When the waves of conflict around him and within surged high, the tempter would say to him, “Martin, you’re a hopeless, stubborn, prideful, ignorant, arrogant, no-good sinner.” And Luther would reply, “True enough, devil, but I have been baptized.” Luther wrestled with a host of demons, the expectations of many, and his own passion for the gospel truth, and I imagine that many a morning, perhaps every morning when he washed his face he paused and whispered, “I am baptized. Christ has made me his own. I belong to God.”

Not a bad habit. In the morning, when you step into the shower, and the water runs over your head and shoulders, pause for a moment to remember your true name and say it, “I am God’s beloved child and God delights in me.” What a way to start your day!

I want to close by reading again some of the lines from the book of Isaiah where God also speaks in the first person. These words were first spoken to a tiny, miserable and insignificant band of uprooted men and women who felt utterly abandoned by God: Do not fear. I have redeemed you. I have called you by name. You are mine.

These beautiful words were first spoken to Israel in exile, but in the end they open to include all of God’s sons and daughters in the great homecoming from all our exiles: Do not fear, for I am with you. I will bring your offspring from the east, and from the west I will gather you. I will say to the north, Give them up, and to the south, Do not withhold. Bring my sons from far away and my daughters from the end of the earth — everyone who is called by my name, whom I created for my glory, whom I formed and made.

That is the end of the story: God’s sons and daughters knowing themselves and one another by their true names. Thanks be to God.