You can write the same words in three-foot tall letters on a billboard, or with a stick in the wet sand on the beach, or with brilliant ink on a beautiful piece of paper, that you fold and mail in an envelope. The words remain the same, but the different ways they come before our eyes open windows to very different meanings.

The words spoken to a group of friends at the dinner table can be repeated verbatim to a crowd of thousands in a stadium, amplified so that even people on the end of the parking lot can hear them, but they are not the same words anymore.

Jesus said, “I am the way, and the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.” It matters greatly when and where Jesus referred to himself in this way: It wasn’t at the beginning of his ministry, but on the evening before his crucifixion. He didn’t shout these words while driving money changers and merchants from the temple; he spoke them in the same room where he had just washed his disciples’ feet during supper. Jesus said these words to men and women who had been with him for some time, who had found life in his presence, and whose hearts now were troubled by the thought of his imminent departure. Who would teach them? Who would guide them? How would they follow a Lord who was no longer there? “Lord, we do not know where you are going. How can we know the way?” Jesus didn’t compose one-liners for billboard advertising; he spoke to friends who needed comfort and courage for the road ahead.

In the gospel according to John, there is an exuberance and superabundance of language, metaphor piled upon metaphor – light of the world, bread of heaven, water of life, vine and branches, sheep and shepherd – and every word points to and circles around the life of Jesus, the divine Word in the flesh, the revelation of God in this particular human life. Everything in this gospel is an invitation to come and see and abide and love and serve and know and live. Everything in this gospel is an invitation to trust this call to abundant life and to let ourselves be drawn into communion with God. The intimacy of mutual love between Jesus and the one he called Father is not exclusive; it is open to the world, open to us, open to everyone.

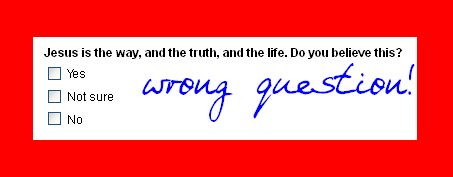

All my life I have been around people who insisted on turning this beautiful invitation into a condition, with a box added to the right of the paragraph that needs to be checked properly in order for salvation to happen.

“I am the way, and the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.” Do you believe this? Check.

The affirmation of the love of God in Jesus Christ is not a rule for the gatekeeper’s manual, but a life embodied in the community of disciples. The divine reality doesn’t appear after someone has checked the correct box or said the magic words; it becomes visible and tangible in the community of Jesus’ friends.

It is, of course, much easier to erect a wall and control who gets in and who doesn’t, than it is to be together, to be with others, mostly very difficult others, in the love of Jesus. Gatekeepers always expect change to be something that needs to happen in others at the transition from outside the wall to the inside. But the love of Jesus breaks down the wall, and his friends expect change to happen in the relationships into which we are drawn by that same love.

I find it very intriguing that in the same chapter in John, only a few lines away from the beautiful words about the way, and the truth, and the life Jesus embodies and offers, only a few lines away, we read about the “Father’s house” and its “many dwelling places.” Now those who cringe every time they hear what has become one of the gatekeepers’ favorite proof texts, suddenly smile. Perhaps “many dwelling places” suggests not only plenty of room for all, but also a great variety of rooms where a great variety of people are at home. For the first readers of John’s Gospel, the metaphor may have offered a way to visualize a community that had room for Jews and Greeks, Samaritans and Romans, Galilean fishermen and urban elites. All of them would be at home, all of them would be together. The Father’s house has room for every nation, every culture and subculture, their music, songs, prayers, cuisine, literature and games – is it too much of a stretch to visualize a house big enough for people of all religious traditions who do justice, and love kindness, and walk humbly with their God?[2] Is it too much of a stretch to visualize a house big enough for all? Isn’t the promise of many rooms in the Father’s house very good news in this world of border fences, high walls, closed doors, and conflicts fuelled by religious differences?

Two short verses, only a few lines apart in the same chapter of John; one a favorite among those who love to emphasize the particularity of our faith, the particularity of our confession, the other a favorite among those who love to emphasize the commonalities among the world’s great religions. The curious thing is that both groups seem to suffer from amnesia. One tends to forget (or overlook) when and where Jesus is speaking, and who his audience is. The other tends to forget (or overlook) that it is Jesus who is speaking, and that this vision of a redeemed humanity at home has everything to do with his particular way of revealing mutual love as the character of God and the power that creates and heals community. There is nothing generic about the Father’s house; it has Jesus’ name written all over it. Wiping the name off the door is no way to invite our neighbors to come in, but neither is telling them that they have to become like us for the sake of their salvation.

John tells the gospel of Jesus Christ with a unique extravagance of language and image that calls us to trust that the Word of God became flesh and dwelled among us so that we in turn might dwell in God, now and always. In John’s telling the gospel is an invitation to fearlessly rely on Jesus’ relationship with us and his love for us. The deeper our trust in him, the better equipped we are for encounters with our Buddhist, Hindu, or Muslim neighbors. Rather than wipe Jesus’ name off the door in order to be more welcoming, we must trust more deeply in his name in order to know the Father’s house in the first place.

Every religious tradition has its fearful gatekeepers who insist that pure religion can be maintained only in a ghetto or compound, and they are not entirely wrong. As soon as we begin to listen to each other and talk about the things we hold sacred, we open ourselves to change. It becomes harder to maintain our stereotypes and preconceptions about each other. We may even change the way we understand and live our own faith. Again, the deeper our trust in Jesus Christ, the better equipped we are to encounter our neighbors with genuine curiosity and a desire to know them. We can trust that whatever transformation occurs in the encounter and the conversation, in them or in us, or, most importantly, between them and us – we can trust that such transformation is the work of the Spirit of Jesus who draws us into God’s future.

On that night when the disciples were uncertain how they would follow a Lord who was no longer there, Jesus told them that he wasn’t going away, but rather ahead of them. “Do not let your hearts be troubled. Believe in God, believe also in me. In my Father’s house are many dwelling places. If it were not so, would I have told you that I go to prepare a place for you?” Jesus is going ahead of us to make tomorrow a place where all of us are at home. No matter where the long road will take us next, we believe the journey of discipleship will lead us home.

[1] John 13:34-35

[2] Cf Micah 6:8